EPIC Oriental Focus Fund: China – last chance saloon?

EPIC Oriental Focus Fund

December 2023

China – last chance saloon?

Relations between the world’s largest two economies have been in retreat for five years across a broad range of issues – Taiwan, technology and trade to name just three – although the recent meeting between Presidents Biden and Xi appears to have drawn something of a line under the recent period. The economic battle between these two economic titans extends far beyond Nvida’s chips but it is worth remembering that China remains an incredibly important export market for the larger, richer Asian economies as the chart below illustrates. It goes without saying that Japan, Australia, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore remain key US Allies in the region. China also remains a huge market for the West – annual exports by Europe and US to China stand at circa $290 billion and $150 billion respectively.

It is also worth noting that China passed a significant milestone last year. For the first time, it traded more with developing countries (generally referred to as the “Global South” these days) than with the US, Europe and Japan combined. This development has been driven in large part by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which was launched by President Xi a decade ago.

The US and China have much in common apart from their sheer economic size. They are the two biggest producers of greenhouse gases, and both are running consistently elevated fiscal deficits. We start with the latter.

Debt

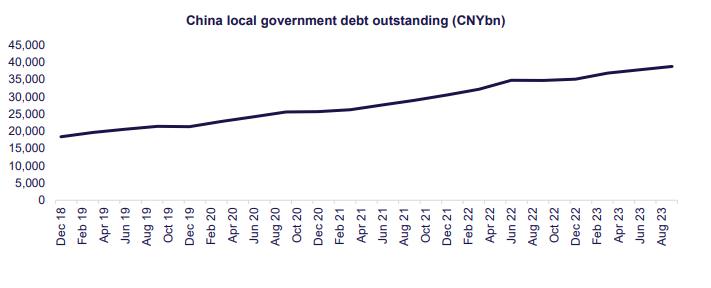

The annual US fiscal deficit over the past 15 years has averaged 5.85% of GDP. While the official annual Chinese budget deficit averages 2.78% over the same period this excludes local government debt and various other off balance sheet items. The true number is at least double that, i.e., similar or worse than the US. The preceding chart illustrates the doubling of local government debt since December 2018.

In mid-October Reuters reported that the Chinese authorities have told state-owned banks to roll over existing local government debt with longer-term loans at lower interest rates as part of Beijing's efforts to reduce local government debt risks. Driven by the deepening residential property crisis, over-investment in infrastructure and the huge costs related to the COVID-19 pandemic, debt-laden municipalities represent a major risk to the world's second-largest economy. Local government debt reached 92 trillion yuan ($12.6 trillion) or 76% of GDP in 2022, up from 62% in 2019.

This, however, is only half the problem. Land sales to residential property developers have, historically, represented a significant proportion of local government revenues. The percentage is falling but for the wrong reason – cash strapped developers currently have neither the cash nor the desire to increase their landbank. While commentary on the subject is changeable, it is increasingly clear that the banks – led by the big four – will be required to step in to support both local governments and the residential property sector. Chinese regulators are drafting a list of fifty developers who will be eligible for a range of financing solutions. This list, which includes both private and state-owned developers, is intended to guide financial institutions as they weigh support for the industry via bank loans, the purchase of debt instruments and equity financing. The priority is to provide the badly needed liquidity to enable the completion of stalled developments and deliver the units to their buyers.

Old hands will remember the raft of uncompleted property projects across Asia in the early 1980s in the aftermath of the commodity boom of the late 1970s with the half-built Gateway City in Singapore my particular poster child on my first visit to the city in 1986. Then there were the property and banking collapses across Asia during the 1997 Asian Crisis. Bangkok, in particular, was littered with uncompleted buildings and infrastructure projects for decades.

Does anyone remember Hopewell Holdings? The Bangkok Elevated Road and Train System (BERTS), also known as the Hopewell Project, was an ambitious project to build an elevated highway and rail line from central Bangkok to Don Mueang International Airport. The project was initiated in 1990 by the Thai government and awarded to Hopewell Holdings, a Hong Kong-based construction company. Construction began in 1990, but the project was plagued by problems from the start. The Thai government was slow to approve the project's design, and there were also disputes over land acquisition and compensation. As a result, construction was delayed and the project's costs began to escalate. In 1992, the first government of Anand Panyarachun suspended the project due to concerns about its cost and environmental impact. The project was restarted in 1994, but it was again suspended in 1996 due to legal disputes between the Thai government and Hopewell Holdings. The project was finally cancelled in 1998, after only 10-13% of the work had been completed.

The “crocket hoop” supports for the proposed elevated highway became a three-decade eye sore known locally as “Thailand’s Stonehenge”.

A similar fate can be easily postulated for China, but the most recent policy response may well prove effective. Best described as “extend and pretend” or, arguably, outright quantitative easing. The People’s Bank of China is likely to provide at least one trillion yuan ($140 billion) in low-cost funding to construction projects via so-called Pledged Supplemental Lending (“PSL”). The PBOC will provide cheap long-term loans to policy banks to fund lending to the housing and infrastructure sectors. Unlike QE programs undertaken by the Federal Reserve and others that involved large-scale bond buying to push down yields, China’s version is more targeted. PSL was used between 2014 and 2019 to help fund a home building spree, leading some economists to describe it as Chinese-style QE because of the resulting creation of money and expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet. We don’t disagree with this conclusion but make the point that stabilising the residential property market is, without doubt, the key to mobilising domestic consumption which remains the principal driver of growth in the Chinese economy.

We recently disposed of portfolio holding China Merchants Banks. We owned the company on the basis that it was best in class within the banking sector, a view we still hold. However, our view on the sector has cooled following the new PSL policy measure. Despite this sector-specific shift in sentiment we, unlike the baying multitudes of other international investors, remain broadly positive towards the China asset class. There are still a large number of highly profitable and fast-growing concerns up for grabs at (increasingly) favourable valuations. We believe it is noteworthy that five of our top ten performers thus far this year are Chinese companies, four of which (JNBY Design, Yadea Group, Shanghai Baosight and China Yangtze Power) are entirely domestically focussed. I am typing this report on my aging Think Pad produced by Lenovo, a truly global business, which is the fifth China holding in the top dozen.

Make no mistake – the residential property crisis, rapidly rising debt levels, unconventional policy actions and deteriorating demographics remain formidable economic headwinds for China but, as you will read in the next section, when China decides on a course of action it rarely pays to stand in the way.

We should all fervently hope that China succeeds given its central role in the global economy. Like it or not, China’s economic future will continue to have a direct impact on every country and every individual. Be careful what you wish for, Schadenfreude has a nasty habit of biting you in the back! In the 1997/98 Asian/EM Crisis musical chairs competition the loser was a little-known concern called Long Term Capital Management. That woke the Fed up!

Renewables

As the tens of thousands flock to the UAE for COP28 we note that, at the time of the first major climate change conference (Rio de Janeiro, 1992), China was one of the least developed nations globally. Its per capita income was below the likes of Haiti, Niger and Pakistan and China’s exports were smaller than those of Sweden or Austria while its airports had fewer daily flights than Norway’s. China’s emissions were just 12% of the global total. These facts are taken from an excellent article by Bloomberg’s David Fickling and are a useful reminder of how rapidly China has developed over the last three decades.

It is true that China burned more coal last year than the rest of the world combined and continues to rely on the fuel for more than 60% of its electricity generation (according to the IEA). Even with China’s frenzied adoption of clean energy, solar and wind currently delivers only 10% of China’s electricity needs.

China will install more than 300 gigawatts of solar and wind capacity in 2023. This is almost double the installations last year and, to put this into perspective, compares to the total global installation of solar and wind of 338 gigawatts in 2022. Solar projects under construction or with secured financing will almost triple installed capacity, likewise wind projects under construction or with secured financing will more than double installed capacity. Bloomberg New Energy Finance recently forecast that China’s renewables capacity will triple by 2030 – we would bet large on China smashing this forecast.

Indeed solar, wind, nuclear and hydro capacity is already approaching a level where it can not only meet but outpace the growth in energy demand in China according to Lauri Myllyvirta of Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. Lauri believes that, if the tempo of deployment is sustained that China’s emissions will fall next year and, potentially, “enter into a structural decline”. This is best illustrated by the Chinese auto sector where EV production continues to gain market share, growing 28% y-o-y in October compared to the 9% growth in total vehicles. The rapid growth in Evs is making a dent in gasoline demand for the first time. EV’s now account for 8.7% of vehicles on the road versus 5.5% a year ago. In itself, this knocks circa 3% off gasoline demand and resultant emissions.

Finally, it is worth noting that this renewable focus extends beyond China’s borders. The Belt and Road initiative is pivoting more toward renewable energy according to a new study from Wood Mackenzie. Renewables now account for 57% of overseas development projects that are currently planned or in construction, compared to only 37% over the last decade.

Henry Thornton

Fund Manager, EPIC Oriental Focus Fund