Bank of England losses add to the Chancellor’s woes

The Rt Hon Sir John Redwood has been a long-standing member of the EPIC Investment Partners Advisory Board, providing valuable insight into the UK investment landscape, as well as the macro backdrop. John is a well known commentator on governments and economies, with long experience of investment markets. We are delighted that he will now share his expertise with our broader network through exclusive thought leadership pieces.

Please enjoy Sir John Redwood's first article under the EPIC banner: 'Bank of England losses add to the chancellor's woes'. In this topical paper, John charts the benefits and pitfalls of the Bank's Asset Purchase Facility and its consequences for the market.

The Bank of England's legal status and aims

The Bank of England is 100% owned by the state, led by a Governor appointed by the government and ratified by Parliament. The Governor reports to Parliament's Treasury Committee on his actions and policies. Parliament legislates to reset the Bank's aims and tasks when it wishes.

The Bank has under its current legislation an independent status to set the key base short term rate and to publish its own economic forecasts. It made large purchases of bonds (£895bn at peak) in response to the banking crash of 2008, briefly after the Brexit vote, and on a large scale during Covid. This was a joint policy of government and the Bank. All purchase programmes required Chancellor sign off with the grant of full Treasury indemnity against any losses the Bank might incur on the bonds.

The main aims of the Bank are to keep inflation at around 2% and to ensure financial stability in the UK markets and banking system. It had a good record on inflation in the decade following the banking crash of 2008, against a benign deflationary world background and with plenty of Chinese competition in goods helping keep prices down. Like the Fed and ECB, but unlike the Swiss, Japanese and Chinese central banks, the Bank of England presided over a surge in inflation this decade, hitting a peak of 11% in late 2022 against the 2% target.

The Bank did not keep markets stable in 2007-9, when there were violent convulsions in the banking system, as in the US as well. There was a short crisis in the UK in late 2022. Markets were driven down by rises in official rates here and in the US, an expansionary budget which was reversed, the Bank's announcement of a major sales programme of gilts and the plight of pension fund investments in geared bond funds. Pension funds had to sell bonds to cover losses and meet calls on their leveraged positions. This forced the Bank to temporarily reverse its bond sales plans and to buy bonds again to stabilise the market.

The Bank and the Asset Purchase Facility

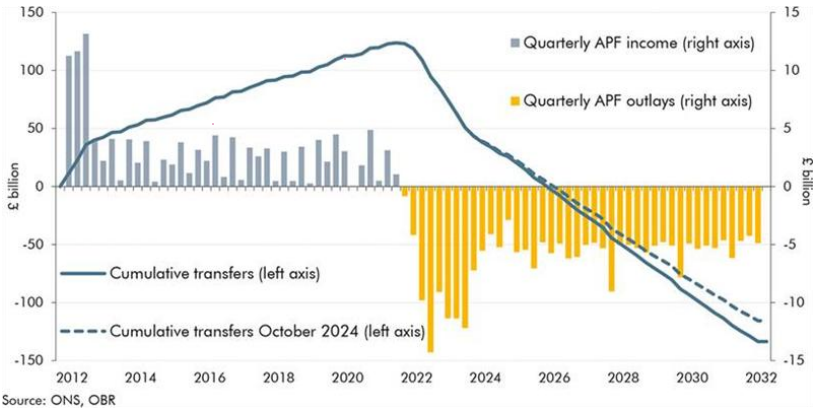

The joint government/Bank bond portfolio was acquired by the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) at the Bank. As it bought bonds from the market, more cash was deposited with the commercial banks, who in turn increased their deposits with the Bank of England. In the early years of the APF, with interest rates falling, the Bank made money on the difference between the amount of interest it earned on the bonds and the lesser amount it paid out for the deposits. Up to mid 2022 the Bank was paying its profits (£123bn) on this over to the Treasury, who spent the cash. When rates started to rise the Bank moved into loss on the portfolio, as the low interest rates it had locked in by buying the longer term bonds were below the higher and rising level of interest on the deposits it held from the commercial banks. The Treasury had to start paying out for the losses.

The Bank added to the losses by proceeding with a programme of bond sales into the market. The bonds were well below the purchase price they had paid, as interest rates had gone up a lot, depressing the price of the bonds. The long dated bonds were often more than 50% down on purchase price and recorded large losses which the Treasury is now paying. No other central bank that had bought up bonds to provide stimulus during Covid lockdowns has been selling bonds at a loss. They wait for the bonds to mature, when they get back the original issue price of the bonds. The closer a bond gets to maturity the closer the market price will move to the original issue price, reducing the losses at a time of higher interest rates.

In 2023-24 the UK Treasury paid £44.5bn to the Bank for bond losses in the APF. The Office of Budget Responsibility is forecasting losses of £257bn from mid 2022 to mid 2033 when they expect the portfolio to be wound up. These losses are now becoming a matter of public debate, with some urging the Bank and government to take action to reduce them and save the Treasury some money. The other trading profits and losses of the divisions of the Bank are very small in comparison to the APF losses.

The Bank deliberately paid too much for the government debt or bonds it bought to drive their prices higher, often paying well above the repayment value of the bond in order to get interest rates well down.

What are the Bank's options on bond losses?

The Bank is currently incurring three types of loss. There is the loss on sales in the market at depressed prices. There is the lesser loss on maturity on bonds bought above issue value. There is the running loss on the interest differentials.

There is nothing the Bank can do to avoid losses on maturity. The private sector is the winner as they sold the bonds to the Bank at a high price and can buy them back at a lower price when new replacement bonds are issued for the maturing ones.

The Bank can suspend or cancel its bond sales at a loss. It does not argue there is a necessary monetary purpose for the sales and is out of line with other central banks. Holding them for longer means continuing revenue losses on the interest differences, but avoids large one off up front losses. Future interest differential losses may reduce as interest rates fall. Capital losses will be much reduced by holding.

The Bank can change the amount of interest paid to commercial banks on their deposits. The European Central Bank (ECB) changed its policy in 2023. It pays no interest on a specified minimum level of reserves a commercial bank has to keep with the Central Bank. It has a lower deposit rate from its lending rates to reduce its losses. The markets accepted this meaner treatment of commercial banks in its system.

Some Bank of England critics think it should return to the older system when it did not pay interest on reserves. This would be a much tougher policy on the banks than the ECB one, cutting bank profits and income considerably, much as a bank tax would. This might have adverse market consequences and could have an impact on credit growth and general economic growth. Banks would need to balance the wish to withdraw reserve deposits and make better use of them with the impaired profit and cashflow which could affect their capacity to lend.

What might the Bank do?

It seems unlikely the Bank will suddenly remove all interest on reserves, as they tend to move cautiously and would not wish to be seen to be following Reform party policy. The Bank may, with behind the scenes government encouragement, take more limited action to reduce some of the losses. This they could most easily do by postponing long bond sales. The Bank will be concerned at how longer rates have risen this year and are now consistently higher than in the late 2022 period of bond volatility. They are less likely to create a minimum reserve requirement with no interest, as they have written about how they find it difficult to judge what the correct level of reserves should be.

Markets will be watching carefully the increases in spending announced as part of the Spending Statement and considering what budget action will be taken later this year to ensure conformity with the Chancellor's fiscal rules. There is general agreement that more tax revenue will be needed to keep to the requirement to balance the revenue account later this Parliament. For the time being the UK offers higher rates than the US, Euro area and Japanese bond markets provide, whilst we await clearer news on the trajectory of future spending and borrowing. There is likely to be more negative speculation before the budget reveals more about how the revenue side could get closer to matching the increased spending.

The Bank has allowed too much inflation and is now keeping longer term interest rates higher for longer as it continues to sell so many government bonds. Its large losses invade the budget arithmetic and add to the fiscal pressures which are impeding better UK growth.

About the author

The Rt. Hon Sir John Redwood has been a long-standing member of the EPIC Investment Partners Advisory Board.

John is a well known commentator on governments and economies, with long experience of investment markets. Trained as an analyst at Robert Flemings, he moved to N.M. Rothschilds where he became a Manager and Director of pension and charitable funds and Head of Equity Research. He was seconded to become Head of the Downing Street Policy unit before chairing a large, quoted UK industrial business. He served as an MP and a government Minister.

In 2007 he set up Pan Asset with a colleague, an investment management business that pioneered active/passive funds and models in the UK. Following the sale of the business to Charles Stanley, a quoted investment manager in the City, he became their Global Chief Strategist advising on non-UK markets and economies. He also ran a demonstration fund for the FT, writing articles about it and illustrating the use that can be made of ETFs in portfolios.

He is now an adviser to EPIC, providing insights into the big investment issues of the day from the debt and spending problems of the major governments to the green and digital revolutions which have so much impact on equity markets. He is a Distinguished Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, where he helps with their Endowment investments and gives occasional lectures on modern economics and politics.